- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

- Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

Satellite positioning GNSS, GPS, GALILEO… How does it work?

FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE,

THE FUNDAMENTALS

OF GNSS POSITIONING

GNSS satellite positioning is part of everyone’s daily life. It is used in a wide variety of applications, but little is known about how it works.

But how does it work?

THE ORIGIN OF “GPS

We owe the GPS (Global Positioning System) to the American army. In 1973, is created the first satellite positioning technology. Originally reserved for strictly military use, GPS has been freely available for civilian applications since 2000. Over the years, it has become an essential part of society.

And although this technology is often referred to in everyday language simply as “GPS”, it is now more accurate to speak of GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System). Other constellations for positioning use have joined the American GPS.

OUR DAYS

These days, there are thousands of satellites orbiting the Earth. These include the satellites in the American GPS, Russian GLONASS, European GALILEO and Chinese BEIDOU constellations, etc. Not all of them are yet 100% operational. GALILEO and BEIDOU, however, should be operational very soon.

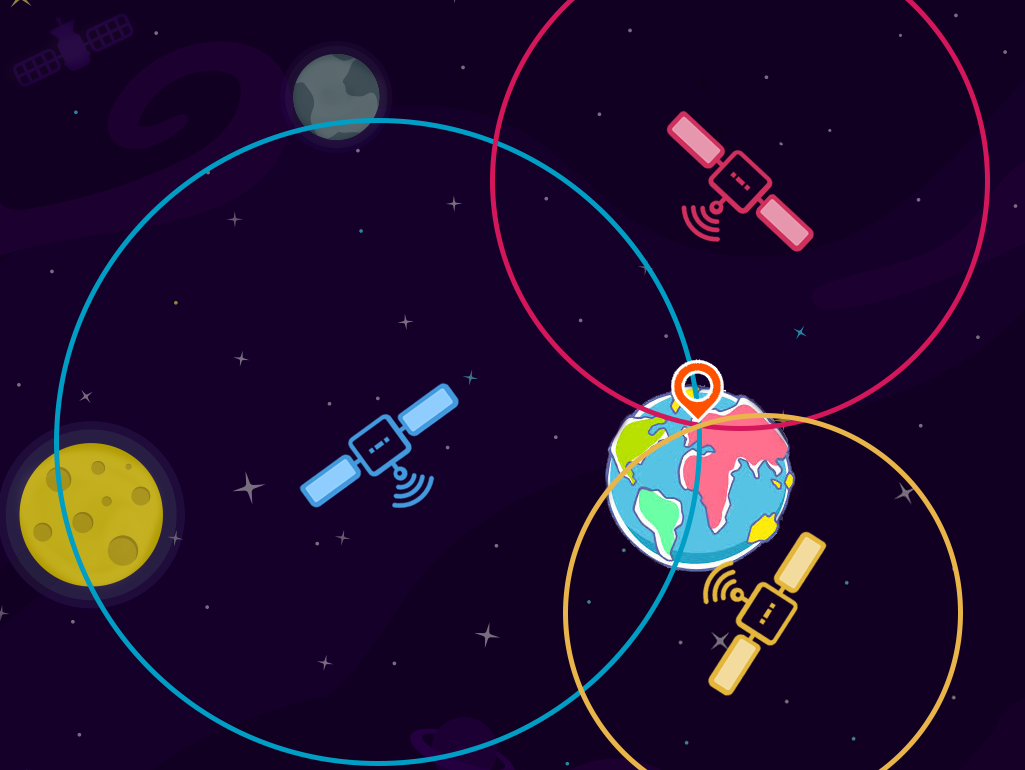

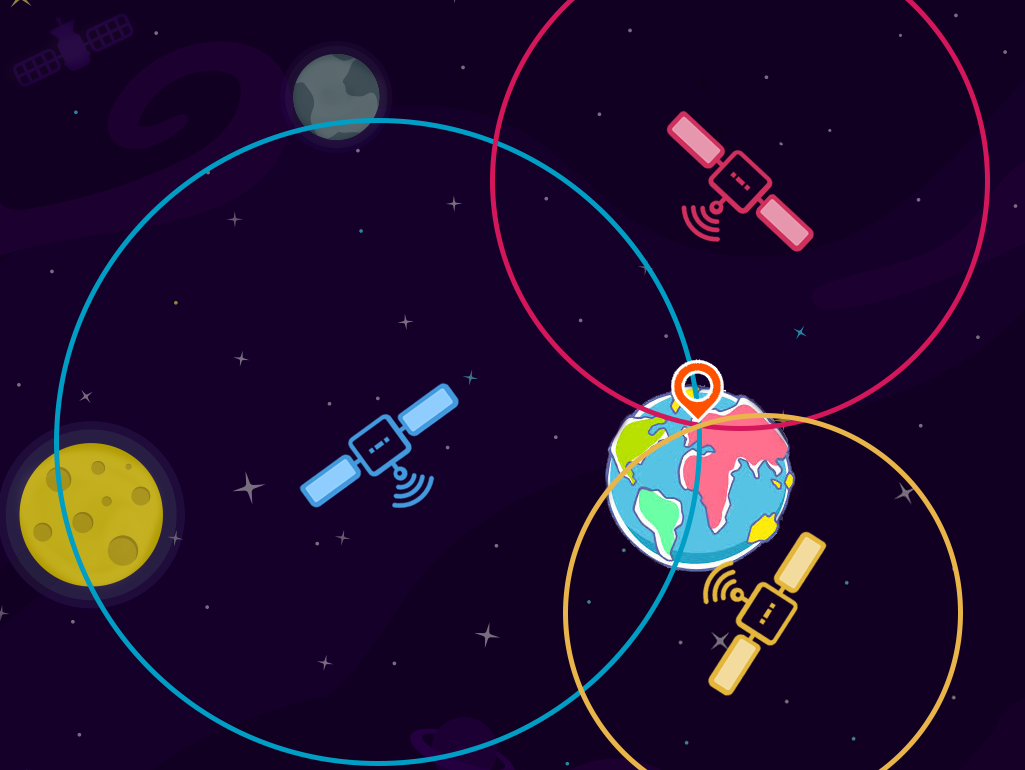

The operating principle is based on the intersection of electromagnetic signals emitted by satellites. The user picks up the satellite signals defining satellite-user segments, the geometric intersection of which is used to locate the user.

Current solutions use signals from several constellations to ensure that they are always operational, wherever and whenever they are needed. This cross-referencing of information means greater precision, near-instantaneous convergence times and 24/7 availability aroundthe globe.

The accuracy of GNSS receivers is metric at best (3-5m). Various calculations and strategies are used to improve this accuracy. TERIA is one of the tools used to increase accuracy. It enables users to obtain positioning with centimetre-level accuracy in real time (1-2cm).

The arrival of new centimetric solutions is opening up new areas of application: autonomous vehicle guidance, maritime applications, drones, etc

How it works in 3 steps :

4 satellites for 1 precise position

Step 1 - The satellites serve as reference points.

The nominal operational constellations GPS, GALILEO, GLONASS, BEIDOU, etc. are made up of several dozen satellites flying at an altitude of over 20,000 km in orbits that are evenly distributed to cover all the continents.

Thanks to this coverage, users can see between five and thirty-five satellites simultaneously, depending on their position on the Earth.

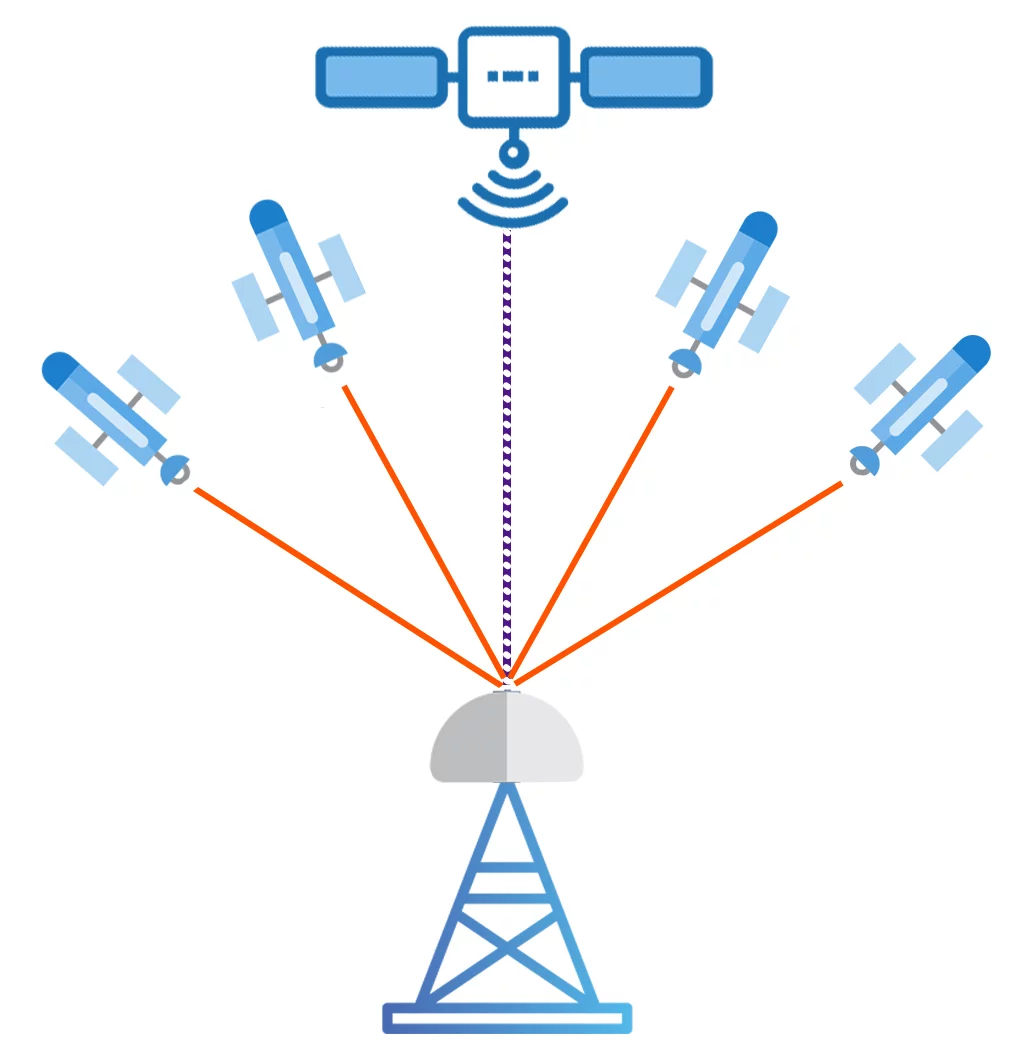

Each constellation is monitored and controlled by control stations that update the information (positions, ephemerides and clock corrections) of all the satellites. The satellites then broadcast their parameters to Earth using electromagnetic waves carrying coded signals.

Step 2 - The distance between the satellite and the GNSS antenna, measured continuously.

The GPS, Galileo, Glonass and Beidou satellites haveatomic clocks that provide extremely accurate dating. The time information is placed in the codes broadcast by the satellite. The GNSS receiver then permanently determines the time at which the signal was broadcast. The signal also contains orbitography data so that the receiver can calculate the location of the satellites. This is known as navigation information.

The GNSS receiver (telephone, topography, agricultural/automotive/aeronautical guidance system, etc.) uses the time difference between the time the signal was received and the time it was broadcast to determine the distance between the receiver and the satellite. The GNSS receiver multiplies the travel time by the speed of light to calculate the receiver/satellite distance.

In this way, a GNSS mobile that receives signals from at least four satellites can pinpoint the precise three-dimensional location of any point within sight of the satellites. To do this, it will use the intersection of these satellite-receiver vectors.

Even in the absence of obstacles, however, there are still significant disturbance factors that require the calculation results to be corrected. The first is the passage through the lower layers of the atmosphere, the troposphere. The presence of humidity and changes in pressure in the troposphere modify therefractive index and therefore the speed and direction of propagation of the satellite signal.

The second disturbance factor is theionosphere. This layer, ionised by solar radiation, modifies the speed of signal propagation. Most receivers incorporate a correction algorithm.

Step 3 - The position is calculated by solving intersection equations between spheres.

The 3rd and final stage is to determine a precise position. The receiver will be able to trilaterate the position from the distance data collected between the GNSS receiver and several satellites.

A GNSS receiver needs a minimum of 4 satellites to be able to calculate its own position. Three satellites will determine latitude, longitude and height. The fourth satellite synchronises the receiver’s internal clock.

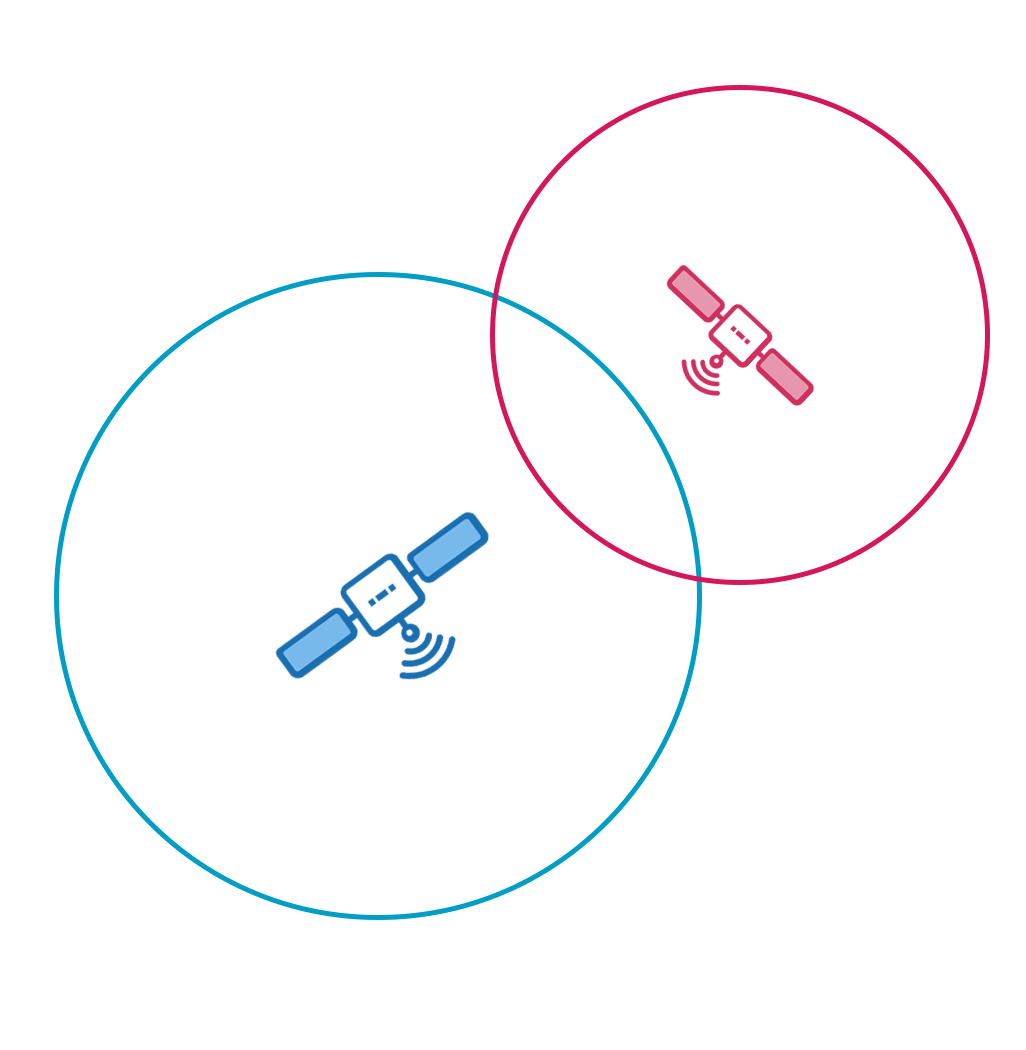

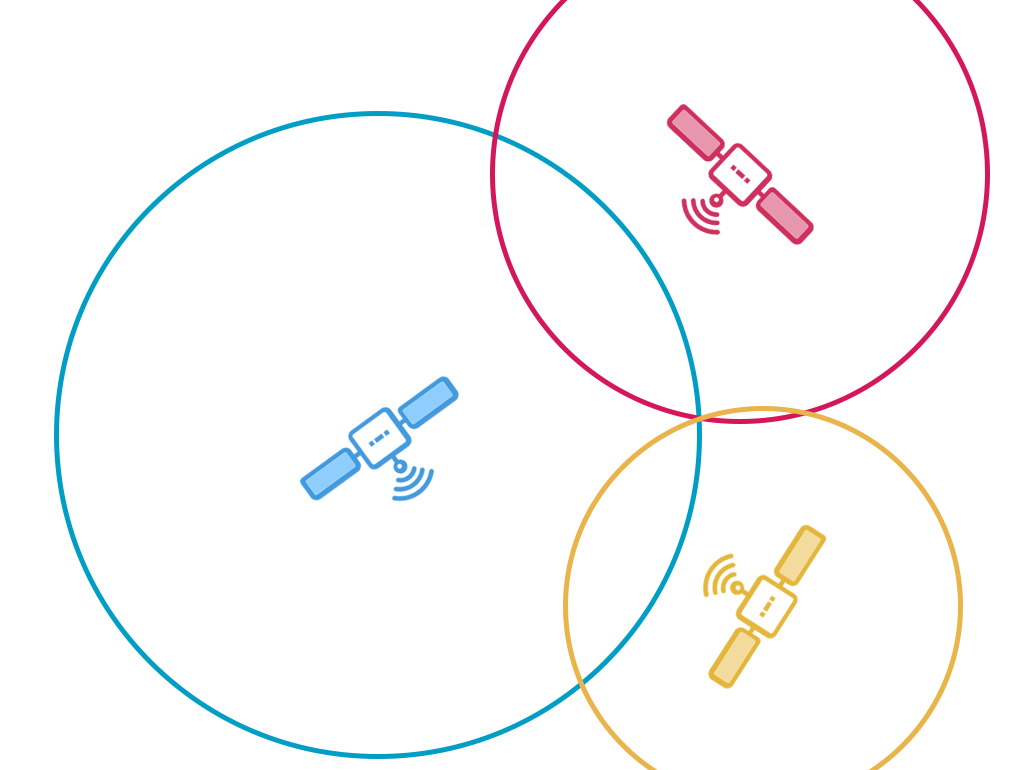

To simplify the demonstration, we’re going to use a 2D plane. The principle will be the same when we move on to 3D space. We’ll just replace the circles with spheres.

EXPLANATION

Let’s assume that the GNSS receiver is 25,000km away from the first given satellite. This means that the GNSS receiver can be anywhere on the 25,000km diameter circle, with the satellite as its centre.

The box will also receive a signal from a second satellite, say 20,000 km away. It will conclude that it is also on this circle. Its exact position will be at the intersection of the two circles, so there are two possibilities.

To determine which of these possibilities is correct, we need the signal from a third satellite. To demonstrate this, we’re going to imagine a circle with a diameter of 15,000km.

At the intersection of these three circles, there is only one possible point in a 2D plane. We have just geolocated our receiver.

To move to 3D, a4th satellite would therefore be necessary, as the intersection of 3 spheres gives 2 points. However, this can be dispensed with because only one of the two points is geometrically coherent. This would leave one possibility to be eliminated.

The use of a 4th satellite is necessary, however, because it provides solutions for measuring signal propagation times. GNSS receivers on the ground have only basic clocks that are not as accurate as the satellites’ atomic clocks. The result is desynchronisation, which needs to be resolved in order to control the receiver-satellite distance and then obtain correct geolocation.

TOWARDS CENTIMETRIC PRECISION

The example refers to the use of four satellites, but GNSS receivers are capable of tracking many satellites at the same time (stations, topographic, telephone, navigation device, etc.). This improves accuracy, convergence time, coverage and reduces the possibility of errors.

On average, a GNSS receiver such as PYX can pick up 7 satellites in the same constellation (14 satellites on GPS – GALILEO). For centimetric positioning, a minimum of 5 satellites is required.

There are currently 129 active positioning satellites available for civil applications:

CONSTELLATION

NUMBER OF SATELLITES

GPS

30

GLONASS

25

GALILEO

27

BEIDOU

44

QZSS

5

IRNSS

8

For applications where centimetric accuracy is essential (autonomous vehicles, bathymetry, topography, etc.), this is not enough. Distortions in signal propagation can lead to errors of several metres. This is particularly true when crossing atmospheric layers.

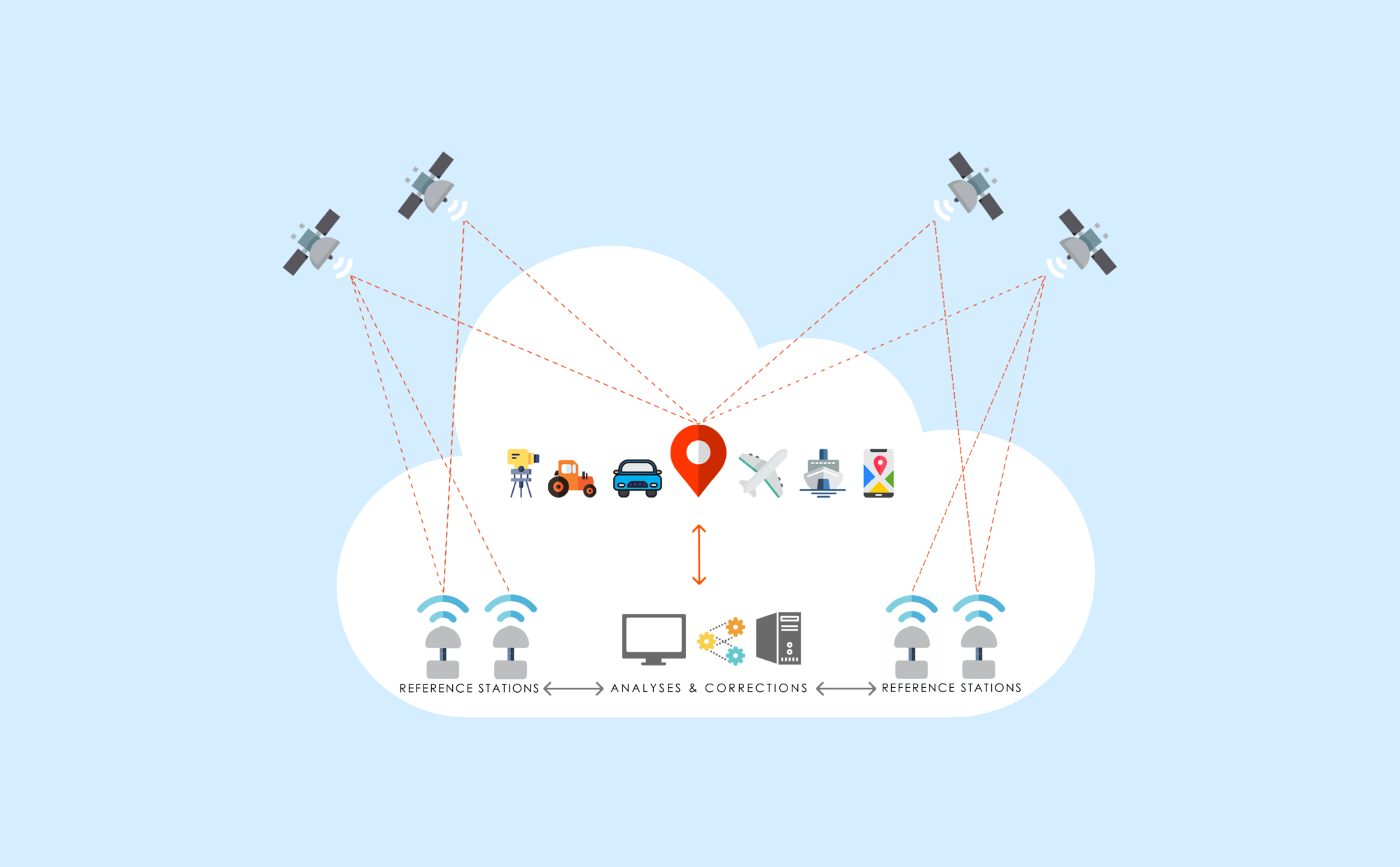

Some solutions, such as TERIA, can correct these measurement errors and provide centimetric positioning of 1-2cm in real time.

They are based on networks of receivers all connected to computing centres, which model all the errors and return corrections (PPP, PPP-RTK, NRTK and RTK) in real time to users.

In order to mathematically locate an object on the Earth in an unequivocal manner, a geodetic reference frame must be defined, expressed in terms of geographical coordinates, which are most often: latitude, longitude and altitude (or elevation) in relation to mean sea level (orthometric elevation) or in relation to a reference surface, usually an ellipsoid (ellipsoidal elevation).

Historically, geodetic systems were determined on the basis of angular measurements and some length measurements. A geodetic system was associated with a geodetic network, a set of points whose coordinates had been determined from terrestrial measurements.

Space techniques have made it possible to define global geodetic systems. The most widely used geodetic system in the world is WGS84 (World Geodetic System 1984), associated with the American GPS positioning system.

Source : couleur-science.eu / gnssplanning.com

Did you enjoy this article?

Feel free to share it.